The Hidden Forces Shaping Our Decisions

Discover how cognitive biases shape your decisions and learn practical strategies to overcome these hidden mental traps. Expert insights from behavioral psychology research.

I sat in a conference room, listening to my colleague present her user research findings. As she spoke, my confusion grew. We had interviewed the same customers and reviewed the same data, yet somehow, we'd arrived at dramatically different conclusions.

My search for answers led me to Dan Ariely's "Predictably Irrational". And since then, i see things differently. I read about experiments where arbitrary social security numbers influenced product valuations and where changing the order of options dramatically shifted people's choices, the zero price effect, the expectation biases, etc.

I got even more interested since my introduction to behavioral economics and cognitive bias in Dan Ariely's book, I've read 8 different books on that same topic. Everything Ariely had written, "Hooked" by Nir Eyal, and the marshmallow test book.

When Two Truths Collide

Down the Rabbit Hole of Behavioral Economics

The Cause

Human brains are wired to seek shortcuts in decision-making. Anchoring, confirmation, bandwagon biases provides a quick and easy reference point that simplifies decision-making, reducing the power and the effort required to process complex information. Belonging and fitting in with those around us, and FOMO (Fear of Missing Out) are also common causes for biases.

The goal here in this article is to let you identify a couple of them, and find ways to break free from these mind traps.

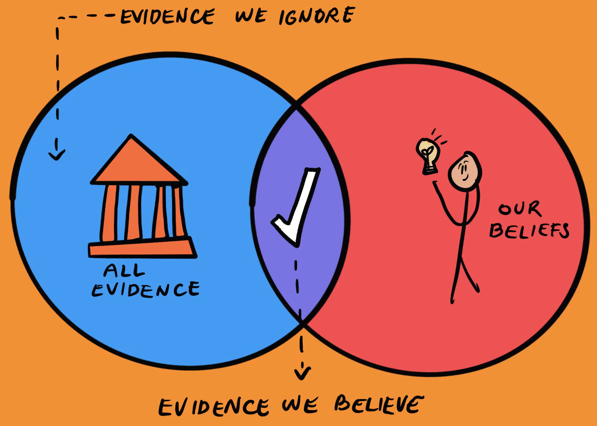

The Blind Spot: Confirmation Bias

Confirmation bias leads us to seek and more readily believe information confirming our beliefs. It's why two people can look at the same data and arrive at opposing conclusions. We get trapped in mental bubbles, dismissing facts that challenge our views.

It is like wearing invisible glasses that filter our world to match our existing beliefs. We don't just passively receive information – we're active participants in creating our own reality bubbles. We eagerly embrace evidence that supports our current views while finding creative ways to dismiss or ignore contradicting information.

Dr. Raymond S. Nickerson's landmark paper in the "Review of General Psychology" (1998) revealed how this bias infiltrates every aspect of human reasoning. From scientists conducting research to doctors making diagnoses, and judges delivering verdicts – no one is immune. It's a sobering reminder that even professionals trained in objective analysis can fall prey to this mental trap.

By being aware of confirmation bias, we can try to look at situations more objectively. It's helpful to consider information that challenges our beliefs, ask questions, and seek out different viewpoints. This way, we can make better decisions based on a fuller understanding of the facts.

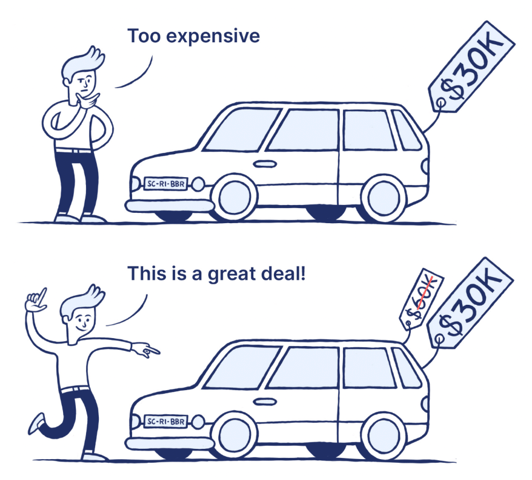

First Impressions… first: Anchoring

Imagine walking into a wine shop. You see two bottles: one priced at $100, another at $30. That $100 bottle has just done something remarkable to your brain – it's become an anchor, subtly shifting how you perceive the $30 bottle. Suddenly, $30 feels like a bargain, regardless of the wine's actual quality.

In 1974, psychologists Amos Tversky and Daniel Kahneman demonstrated this phenomenon through an elegantly simple experiment. They asked participants to spin a wheel numbered from 0 to 100, and then estimate the percentage of African countries in the United Nations. The results were startling: people who spun higher numbers consistently gave higher estimates, while those who spun lower numbers guessed lower.

Think about that for a moment. A completely random number from a spinning wheel influenced people's estimates about an unrelated geographical fact. The implications are profound – our minds grab onto the first number we see, using it as a reference point for subsequent judgments, even when that number is entirely arbitrary.

Restaurant menus are also masterclasses in anchoring manipulation. That $50 steak isn't just a meal option – it's a strategic anchor that makes the $30 chicken dish feel like a reasonable choice. Some high-end restaurants even include an extraordinarily expensive item they rarely expect to sell, solely to make everything else seem more affordable by comparison.

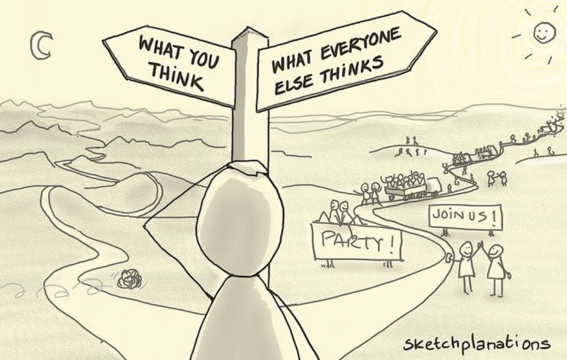

The Digital FOMO: Bandwagon Effect

"Everyone else is doing it."

Five simple words that have launched countless decisions, from childhood playground choices to multimillion-dollar corporate investments.

In the 1950s, psychologist Solomon Asch conducted what would become one of psychology's most revealing experiments. The setup was deceptively simple: participants were asked to match the length of a line to one of three comparison lines. The catch? Everyone else in the room (who were actors) deliberately chose the wrong answer.

The results were stunning. When faced with the group's unanimous but incorrect choice, 37% of participants denied their own eyes and went along with the wrong answer. Even more telling, in post-experiment interviews, many participants knew they were choosing incorrectly but felt an overwhelming pressure to conform.

Why We Jump on the Bandwagon? Our tendency to align with group behavior isn't just social pressure – it's wired into our survival instincts.

The Safety in Numbers Instinct, The Social Proof Shortcut, The Fear of Missing Out.

Breaking-Free

Professional Bias-Breaking Strategies

Document hypotheses before looking at the data

Have multiple team members independently analyze information

Actively seek evidence that contradicts assumptions

Create structured decision-making frameworks

Implement blind evaluation processes where possible

Personal Decision-Making Tools

Keep a decision journal to track your thought process

Create cooling-off periods for major decisions

Practice the "flip test" (consider the opposite of your initial judgment)

Set clear criteria before making important choices

The goal isn't perfection – our brains will always take shortcuts. As Daniel Kahneman wisely noted, "We can't eliminate biases, but we can work to recognize them and minimize their impact on our decisions." The key is building systems that catch these biases before they catch us.